The Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) is committed to providing free, universal access to the rich cultural tradition of Irish music, song and dance. If you’re able, we’d love for you to consider a donation. Any level of support will help us preserve and grow this tradition for future generations.

This programme was first broadcast on TG4 on Sunday 19th May 2024.

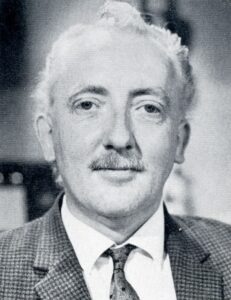

A. Martin Freeman on the Isle of Canna, c. 1940s {courtesy Canna House, National Trust for Scotland).

The very idea of a collection suggests to us a bounded, identifiable reality, an antidote to the flotsam and disorder of life’s entropic processes. We seek to order our world in all that we do, from the stone walled fields of the west of Ireland to the classificatory mathematics and language that organizes whatever knowledge we have amassed in the thousands of years of human civilization. Libraries, those once proud bastions of accrued wisdom may have given way to the light speed world of data sets which we now inhabit and interrogate but even so as the methods of transferring information from one location to another may have become passé and its organization somehow now graduated from the immediate physical realm to something more ephemeral, underneath the gleam of touch screens and silent distant server farms we still live in an organized and collected world. In fact, though the methodology of access and indeed interaction has evolved, our existence today is arguably more than ever dependent on the collection, the gathered, the classified and understood. And our culture depends on these permeable yet bounded containers of knowledge to function in an ordered, predictable fashion. The collection is a representation also of identities, perhaps idealized but still potently able to transmit an idea or ideas that define, explain, illuminate our understanding of ourselves and our world. 109 years ago a certain Alexander Martin Freeman visited the parish of Ballyvourney in County Cork with his wife Aida on a holiday.

A graduate of Lincoln College, Oxford and a native of Tooting in the metropolitan London area, he had become, through his association with his wife, a native of Donegal, quite acquainted with and interested in Irish culture and folklore and the activities that occurred in Irish circles in London in the early part of the century. He was a regular attendee of the then Irish Literary Society in Hanover Square and in time acquired a good knowledge of the Irish language having studied under Kuno Meyer. The trip to Ballyvourney must have had a great impact on the Freeman’s as, on the following year they returned for a visit lasting some three months during which time Freeman spent weeks filling his notebooks with song tunes and words from a handful of singers. These songs would in all likelihood have seen light of day earlier were it not for the onset of the First World War which saw Freeman enlist in the Royal Army Service Corps and being posted to Salonika. On his return from war the detailed editorial work so evident in the collection resumed and what has become known as the great Ballyvourney Collection appeared in the Journal of the Folk- Song Society 1920-21 as numbers 23-25. To quote the great Irish Folk song collector Donal O’ Sullivan writing in the Journal of the Folk Dance and Song Society in 1960 following on the occasion of Freeman’s death in 1959 he says of the collection:

The task of collecting songs from a small group of native speakers in a foreign land requires considerable skill and determination and it is acknowledged that in his efforts Martin Freeman had considerable support from his wife Aida.

One unnamed correspondent quoted by the society in an Obituary to Mrs. Freeman states that:

Freeman himself must also have been possessed of the type of personality that allowed him to gain peoples trust sufficient for them to sit with him for days on end and recall song and story. Apart from the great store of songs that this collection contains Freeman’s own recollections and notes regarding his encounters with his chief informants are both revealing and profound. For instance in page XIX of Volume 6 number 23, he describes for us the four key singers on whom he relied for much of the collection. Of Peg O Donoghue he says the following:

I have always been struck by Freemans last phrase here and have tried to imagine what he may have witnessed as this elderly and clearly beautiful singer achieved a change of state during her performance of the song. In a world now which leaves less and less to chance and less space for the imagined what Freeman does not tell us beyond that word “ecstatic” leaves us with a sense that in fact the experience was an unforgettable one, one which would have to be experienced first-hand and could not easily be conveyed by the writers hand. It suggests a liminal area best left to the moment and to the silent, personal recollection. I have carried that image of the singer achieving a special grace through the act of song with me down through the years as a strange inexplicable, talismanic metaphor for what might be possible in our music, what might be achievable in the performance of these musical objects radiant of an intangible and beguiling beauty.

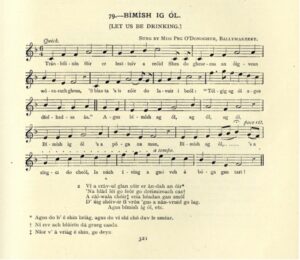

Journal of the Folk Song-Society, 1921 (No. 25; vol. 6, part 5)

This collection is by any measure an extraordinarily rich hoard of song and poetry and apart from the fact that it contains an invaluable core sample as it were of our singing culture more than 100 years ago, the method of its collection, without the means of sound reproduction such as was available at that time, confers upon the work an oddly literary and poetic focus. It also paradoxically, considering the methodology deployed in the transcription process (which to my mind displays extraordinary scholarship and dedication) supplies us with unusual insight into the sonic and timbral character of the Irish language in its common usage at that time. The entire collection is notated using what Freeman calls “The Simplified Spelling of Irish” developed chiefly by the Gaelic Scholar Dr. Osborn Bergin in 1907 as an aid to the learning of Irish. The system is phonetic in nature and Freeman states that its deployment arose from his belief that, as he puts it:

He illustrates his point with the Irish word Amhrán for song as having many variants including:

Aurán, abhrán, úrán avarán, and óran.

Using the approaches propounded by Freeman what eventuates is a collection which can be sounded according to the pronunciation guide which is included in its chapters and when deployed with the translations thus giving us a very accurate and full, sounded picture of speech patterns in that area a century ago. And in my own studies I have found this to have been a key attribute of the collection which gives it tremendous range and aesthetic depth. Freeman concludes on his notes regarding pronunciation:

We are not concerned with the encouragement of Irish learning or the education of Irish Speakers. But the new system is of great value to collectors and students of folk songs, because it provides a means of showing:

(a) Approximately how the syllables are apportioned to the musical notes, and

(b) Exactly how each syllable was pronounced by the singer.

And to know how something is sounded in relation to the music is an invaluable guide in the process of recovering, remaking in sound and re-living the songs contained within the collection’s covers. Reading through the collection I find myself keenly aware of the sound itself, embedded in the phonetic structure as it is through Freeman’s fastidious notation and I am reminded of the breath and grandeur of the spoken language of our forebears and of the syncretic poetic awareness that is alive in the everyday language of these people and what might now seem as their extraordinary engagement with the poetic experience as a normal pattern of their daily existence.

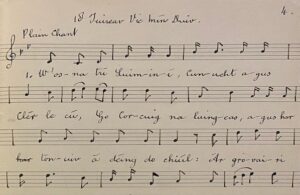

Freeman Collection. National Folklore Collection Archive Box Series DOS/FP/1/2:04

Recently an extraordinary document has come to light – a recording of A.M Freeman himself singing a selection of songs from Ballyvourney, on the Scottish Island of Canna, for his friend John Lorne Campbell in 1951. The recordings are a vivid and telling record of his fidelity and fealty to the songs of the people of that region and of his own keen ear and mastery of their rich song culture. The recordings can be heard on the Tobar an Dualchais website: https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/person/6012

And how was it one may ask, that I came upon this collection and the many treasured songs it contains. That is due in large measure to the arrival in the village of my upbringing – Cúil Aodha, a notable and mercurial figure who towers over the manifest development of Irish Traditional Music in Ireland in the 20th Century – composer Seán Ó Riada.

Seán Ó Riada / Unidentified photographer

The arrival Of Sean O’Riada to this remote corner of Ireland in the 60’s was opportune. In Cuil Aodha at the time he found a society under considerable economic stress with no local industry to speak of and a population whose younger generation, though brought up in an environment of traditional values (which included a latent religiosity and arguably a linguistic and cultural insularity) were beginning to see and move outside it. It was a society to those within it whose cohesion was fraying at the edges under pressure from forces much more powerful than it could on its own muster. Many of the younger singers were toying with the show-band phenomenon and habitual speaking of Irish was on a steady decline. O’Riada’s arrival heralded what I would advance as a deliberate re-activation of the local music culture. This involved an intensive trawl of old collections and in particular The Freeman Collection, the tape-recording of old singers, the learning and adaptation of archive material and then the exposure and celebration of these renascent musical artefacts in public performance not only in the church but also in halls throughout the country.

Cuil Aodha would come to be seen as the last step in O’Riada’s cyclic development as an artist; a journey that brought him from a familial traditional music background through the explorations in serialism of his Nomoi compositions and back again transformed by the spectacular success of his film music settings for Mise Eire and Saoirse to that of a public figure experimenting with and extolling the virtues of a native, ancient and noble music culture and language as he saw it. For some, particularly those who justifiably looked to O’Riada as the last hope for the development of an Irish art music, this atavistic migration would come to be interpreted as a catastrophic failure and betrayal of his true gifts. For the formerly solo singers of Cuil Aodha, mostly drawn from small farming backgrounds his philosophical and musical about turn would be a cultural and economic renaissance. O’Riada’ reputation and panache, in time secured new industries for the region, and gave its music culture a platform and confidence it had never before experienced. This confidence also fed off the other sources most notably the re-emerging nationalism of the northern troubles and a latent re-inscribed sense of nationhood as prescribed by Douglas Hyde and the Gaelic League. These were not difficult energies to harness since the regions surrounding Cuil Aodha had half a century earlier been hot beds of guerrilla insurrection prior to the establishment of the Irish Free State. A cultural re-enactment of the sort promulgated by O’Riada found easy reception in the fertile ground of a place which Republican ideologue and martyr Padraig Pearse had called ‘ the capital of the Gaeltacht’ in a 1908 article in the ‘Claidheamh Soluis’. (Referring to the parish of Ballyvourney)

After Sean O’Riada’s untimely death in 1971, the choir continued under the direction of his then 17-year-old son Peadar and continues to this day. I have often pondered upon O’Riada’s reaction when first he read the songs in the Freeman Collection on the dusty shelves of the library at University College Cork. When that may have happened is not clear but local sources have indicated that upon his arrival to Cúil Aodha he had already scrutinized its contents and had also developed a strong liking for some of its songs in particular. Peg O’ Donoghues rendition of the beautiful Aisling Gheal would become O’ Riada’s party piece on the piano or Harpsichord. It would also be one of the songs first learned from the collection by famed sean nós singer Diarmuid Maidhcí Ó Súilleabháin and eventually by myself. Other songs from the collection also permeated into the repertoire of the choir when performing concerts or Claisceadail as they were known around the country. Songs such as Bímís Ag Ól, Tuirimh Mhic Fhinín Dhuibh, An Habit Shirt and Éistigh Liumsa Sealad became embedded in the corpus of songs that would be performed regularly. Other individual singers subsequently explored the text and found songs that were sometimes familiar to them and at other times newly uncovered gems that had long lain silent awaiting re-discovery. For me it remains a landscape of almost infinite possibility- a truly dynamic and rich resource from which to draw and thus learn and grow.

Iarla Ó Lionáird, May 2024

* This blog features an abridged version of a text which Iarla Ó Lionáird contributed to Dan Trueman’s Substack page: Many Arrows Music. The original text can be found at https://manyarrowsmusic.substack.com/p/cumha-na-cuimhni-loch-lein