The Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) is committed to providing free, universal access to the rich cultural tradition of Irish music, song and dance. If you’re able, we’d love for you to consider a donation. Any level of support will help us preserve and grow this tradition for future generations.

When going to a session of Sliabh Luachra music one would expect to hear the tune types represented on The Star above the Garter (Claddagh Records CC5): polkas, jigs, slides, reels, hornpipes and slow airs. This might seem like a fairly complete mix of tunes – but in fact, the picture was even more varied in Denis Murphy’s younger years. Far from being limited to sets, the dance halls of the era saw a variety of couple dances, including waltzes, mazurkas, schottisches, barndances, flings, military two-step and other varieties. Those dances were beloved by local communities across Ireland but considered foreign and looked down upon by the Gaelic League, which infamously banned set-dancing from its céilís. Like the sets, couple dances were also undermined by the 1935 Public Dance Halls Act – but unlike the set-dancing in the 1960s and 1980s, they did not experience a subsequent mass-scale revival.

However, some of the tunes used to accompany couple dances have survived in traditional music hotspots like Sliabh Luachra. Sometimes they were repurposed to suit the sets, other times musicians remembered they were specifically suited for a particular dance. A few of those tunes have defied classification to this day – and Denis Murphy naturally had them in his vast repertoire.

Another thing that came to Murphy naturally – but has not been featured on any of the commercial recordings to date – was singing. There are privately made tapes of him entertaining house parties with witty stories, ditties and songs. Breandán Breathnach made several recordings of Denis Murphy singing and it was only fair to include one of them here alongside the rarely-heard tunes.

One tune type that would have even the most experienced Irish musicians scratching their heads in search of a definition is the single reel. Not to be confused with “reels played singly”, these tunes would usually be notated in 2/4 but played without the characteristic polka lift. To confuse matters further, most of the tunes that would have been known as single reels by musicians of the older generations are presently played as either polkas or reels.

This situation could perhaps be explained by the fact that there remain no popular traditional dances associated with the rhythm of a single reel, which suited the style of dancing in some of the regions of Ireland and could have been contrasted to what the locals would sometimes refer to as “Clare reels”. In rare cases up until recently, dance masters like Timmy ‘The Brit’ McCarthy (1945–2018) would have requested single reels to be played as the last figure of a set, such as The Jenny Ling – but most modern céilí bands would invariably play regular reels for the purpose.

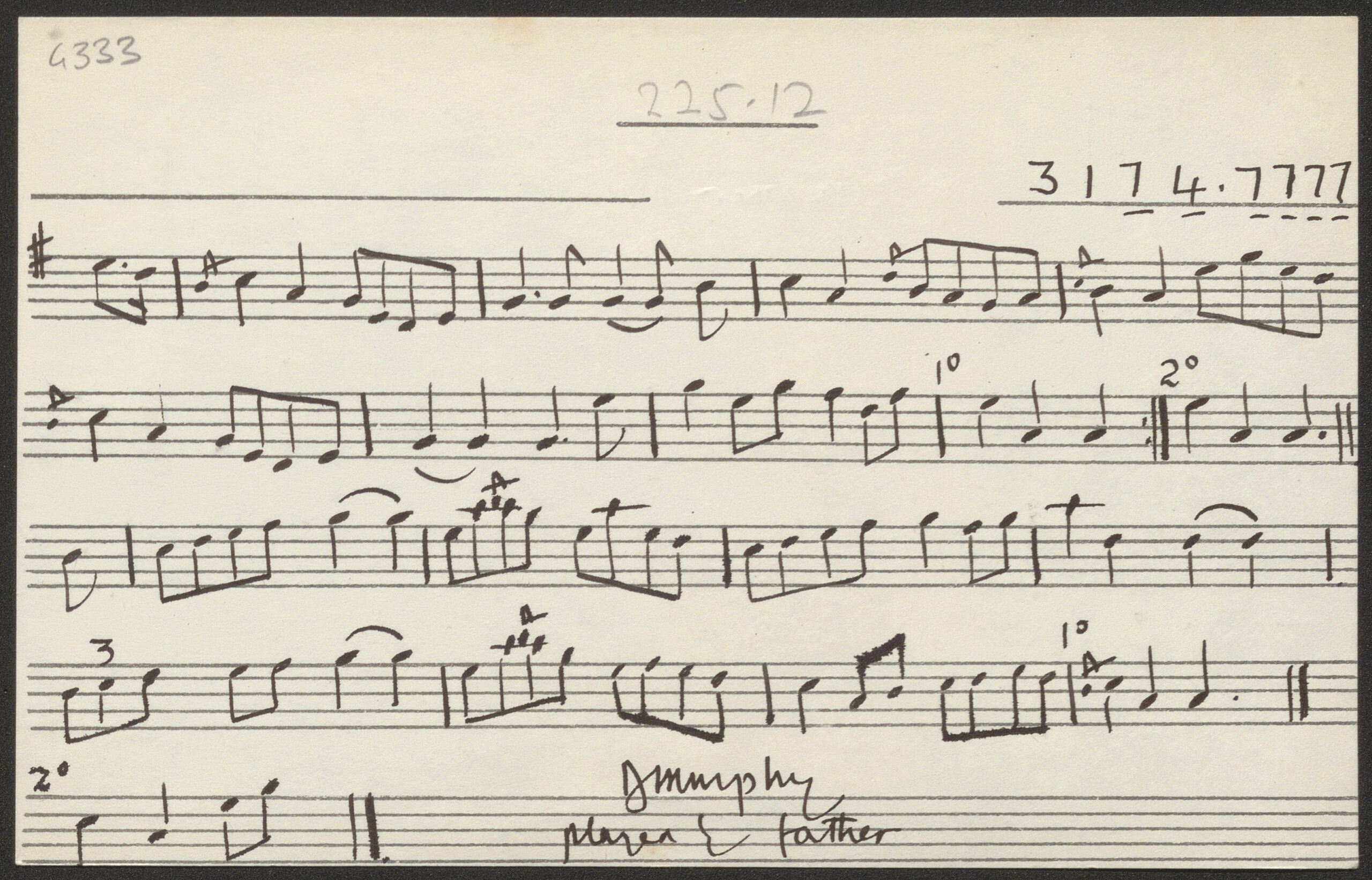

It was all the more interesting to find an old tune identified as a “single reel” in the materials collected by Breathnach (CICD 4333).

[Bill the Weaver’s], single reel / Denis Murphy, fiddle ; transcribed by Anton Zille. (Breandán Breathnach Collection. Reel-to-Reel 30, October 1966)

Denis Murphy played this tune to Breathnach at least twice, in October 1966 and November 1970. He did not offer any specific name for the tune. Curiously, Murphy also played it in a relatively upbeat tempo during the first recording session but chose a deliberately slow tempo for the later recording.

The flipside of CICD 4333 includes a note: “an old single reel played by father”, thus identifying Murphy’s source for the tune as Bill ‘The Weaver’ Murphy. Judging by the additional note “also K2 / 1970” made in the same handwriting and pen colour, Breathnach likely wrote this down after November 1970. The dating is crucial as an additional evidence for the tune type not being incidental or put there in error: by 1970 Breathnach certainly did not call polkas “single reels” and most of the tune-specific information on the cards appears to be quoting Murphy verbatim. It would seem that Denis Murphy purposefully chose to define the tune as a single reel.

This context has apparently been lost over the years, with the tune’s background left open to the musicians’ interpretation. Recorded twice to date since the start of the 21st century, Bill the Weaver’s single reel has been identified as “a set tune / barndance” by Billy Clifford and Gerry Harrington (Now She’s Purring, self-published, 2018) and as a march by Joey Abarta (King of the Blind, self-published, 2023).

Upon further inspection, a tune seemingly sharing the same melody but usually played as a reel can be found under the name of John Egan’s reel. It is associated with the Ballintogher, Co. Sligo flute player John Egan (1903–1989) and is sometimes attributed to him (without evidence). Egan learned to play the flute, the fiddle and a wealth of local tunes in Sligo, playing for the house dances and with a local fife and drum band. He later moved to Donegal and then London in search of work before settling in Dublin in 1937, where he became a key figure of the traditional music scene of the era. Breathnach collected a version of John Egan’s reel from a Sligo fiddle player John Henry (CRE 5, # 142). While any attempts to connect John Egan and Bill ‘The Weaver’ would be sheer speculation at this stage, it is notable that both played in fife and drum bands in roughly the same time period. Discovering the repertoire of those bands would likely result in some fascinating historical finds related to the evolution of dance music.

Dolly Varden was a name given to several traditional tunes played in Sliabh Luachra, including the tune otherwise known as The gypsy princess (now commonly called a barndance but identified as a hornpipe by Denis Murphy and thus included in the Hornpipes chapter). More broadly, it was a name given to most anything in need of being named or advertised in the 1870s and 1880s but in some cases up until the 1930s. A side character of a Charles Dickens’ novel that became iconic in wake of a well-received portrait, Dolly Varden gave name to fashion trends, songs, plays and operas, cakes, a species of trout and, most importantly, to pieces of quadrille music, including polkas, schottisches, waltzes etc.

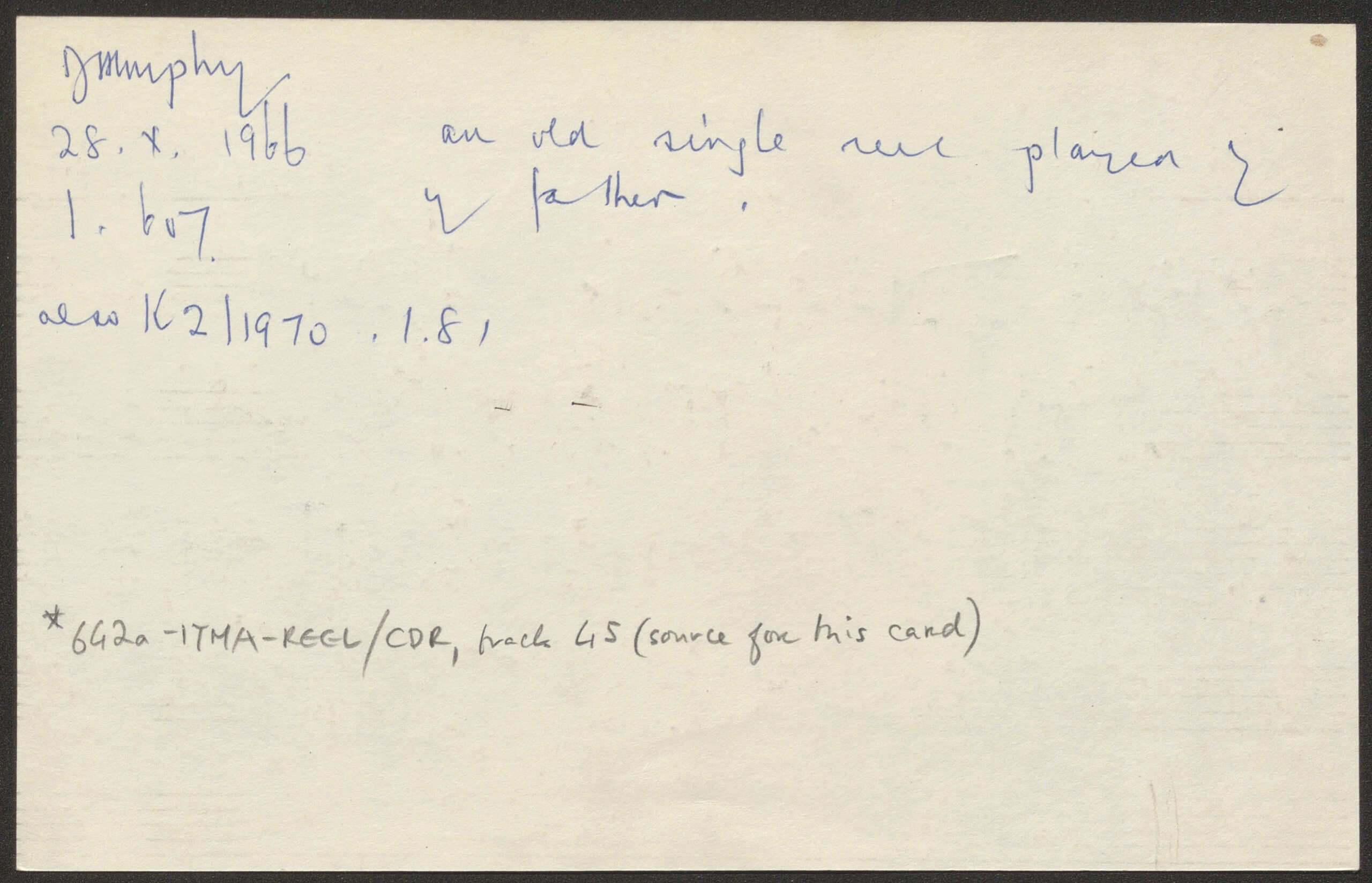

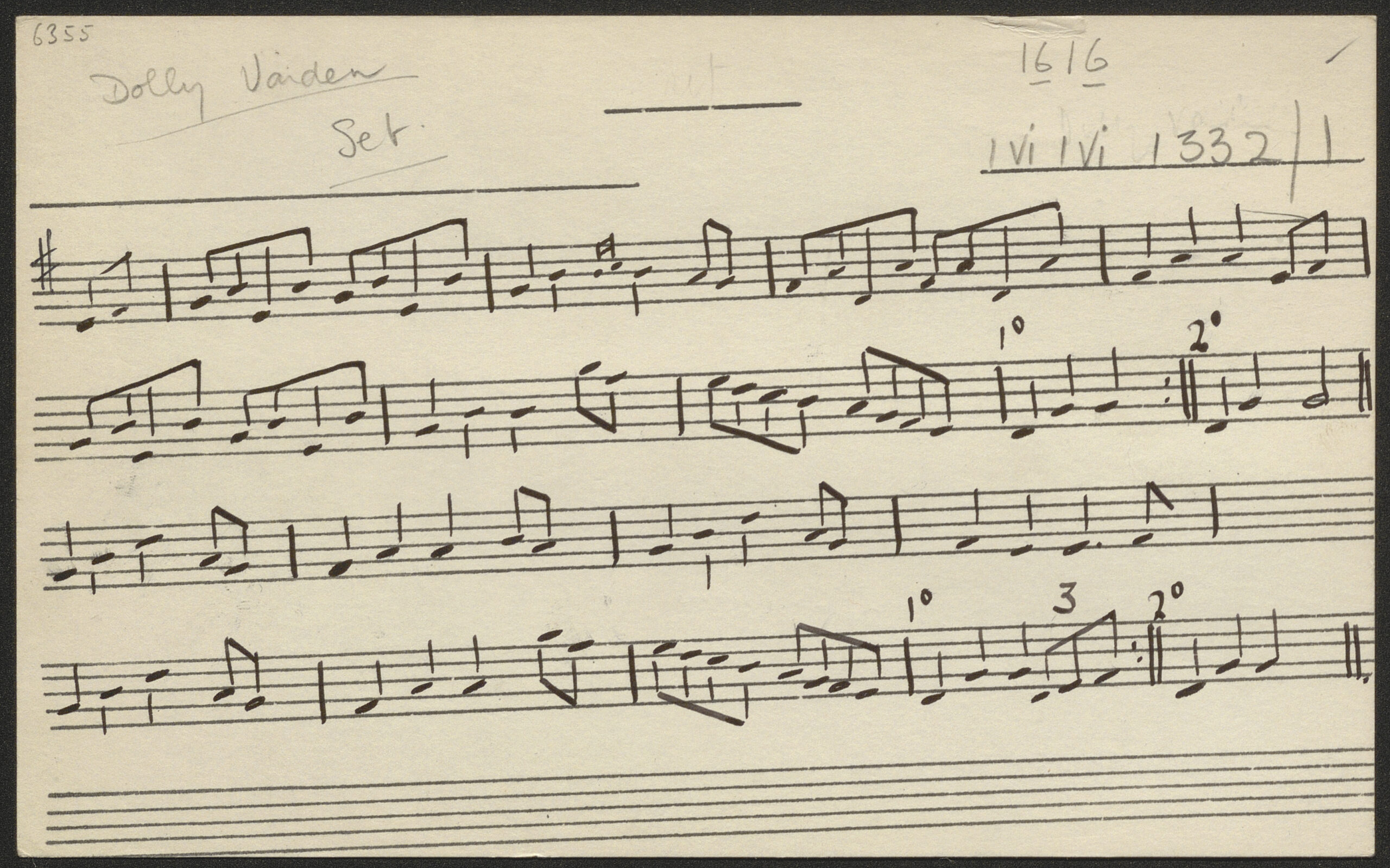

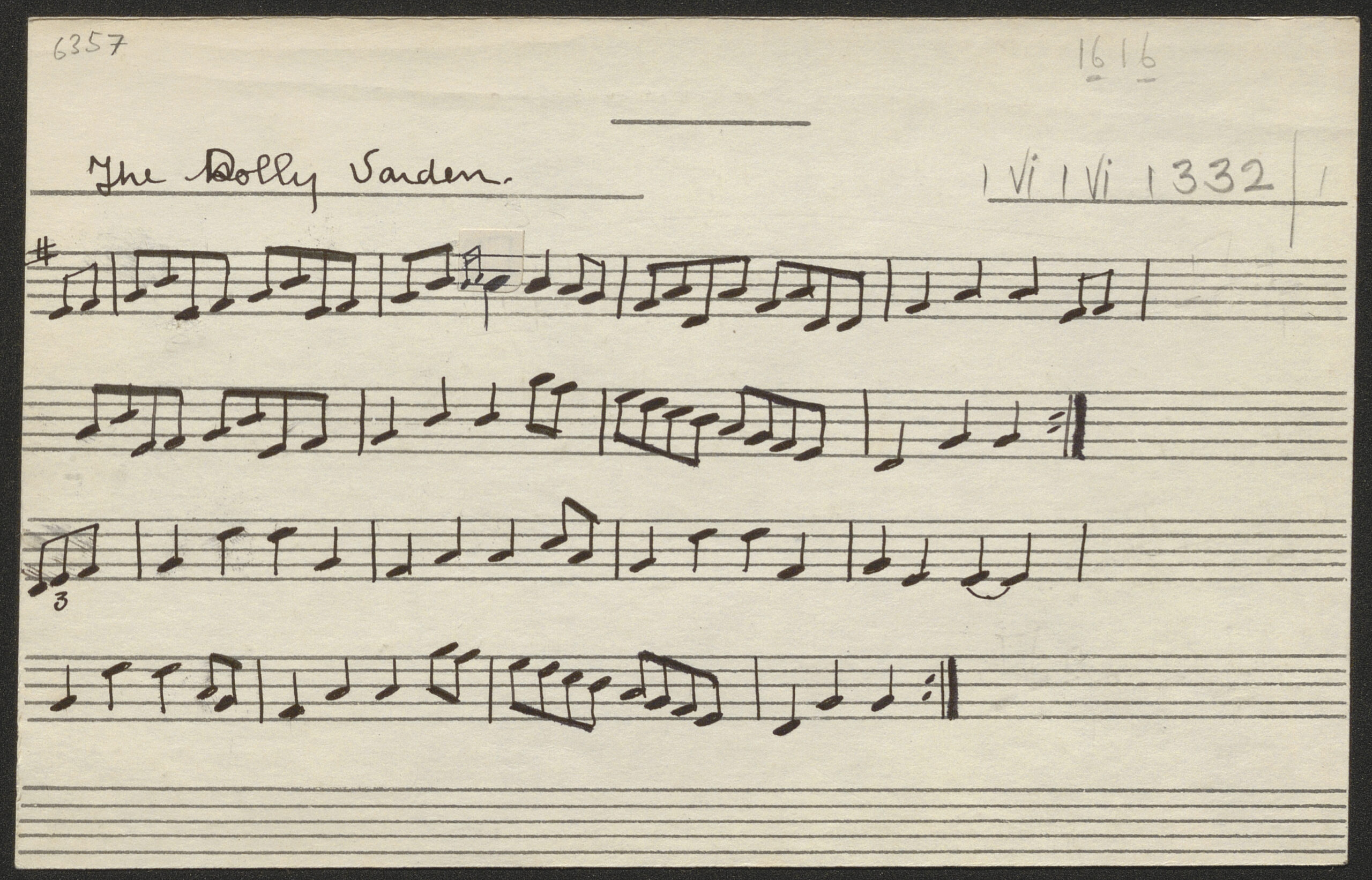

It is not clear whether the tune transcribed on CICD 6355 and CICD 6357 is directly related to any of the Dolly Vardens published for the quadrille or if the title was coined locally to capitalise on an old fad. But the Breathnach materials reveal that this tune was played for the couple dance of the same name.

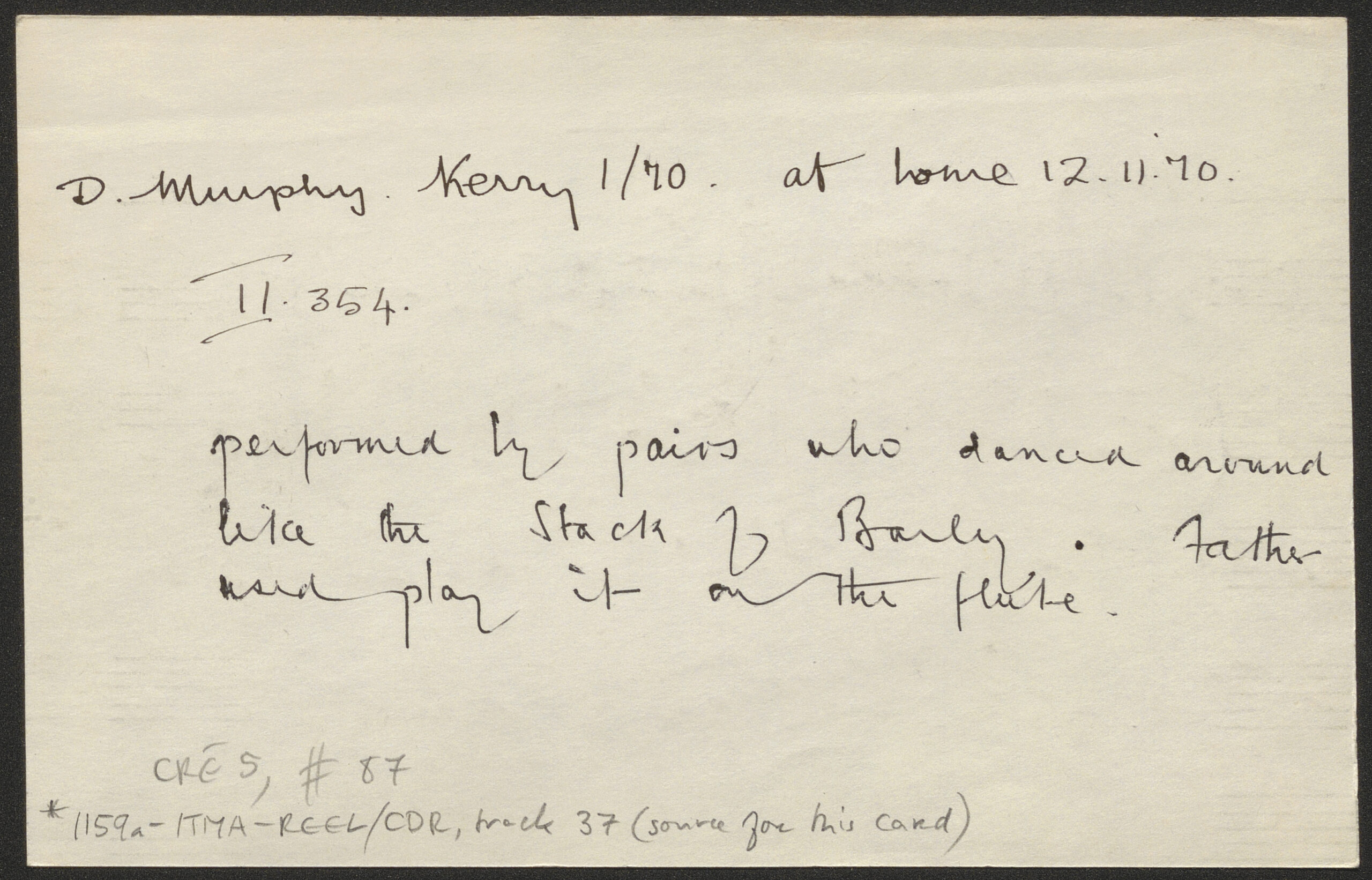

Dolly Varden was “performed by pairs who danced around like the Stack of Barley”, says a detailed note citing Denis Murphy on CICD 6357. Breathnach adds that “father [Bill ‘The Weaver’ Murphy] used [to] play it on the flute”. In the recorded materials, Murphy plays the tune, tied to this now-lost dance, twice, first in November 1967 and then in November 1970.

The tune was later published in Ceol Rince na hÉireann 5 (no. 87), where it was notated as a polka, with a note saying that it was also known as William Clarke in Co. Limerick. Looking at the analogy provided by Denis Murphy, it is perhaps more fitting to describe the tune as a schottische, a barndance or “a set tune in hornpipe time” – just like the dance The stack of barley would variously be described. (Unlike the dance, the signature tune played for The stack of barley is usually called a hornpipe by Irish musicians; it has been recorded by Denis Murphy, Julia Clifford and Pádraig O’Keeffe, among many others).

Flings, it would seem, have all but disappeared from music sessions in Sliabh Luachra – but a few of those tunes were actively played by Denis Murphy and his contemporaries. This includes relatives (or settings) of the iconic northern tune / dance Maggie Pickens, variously described as having originated in Scotland or in Co. Donegal. Murphy played the slide version of this tune that is often called Charming lovely Nancy or An Chearc ar fad is an tAnraith (CICD 1025; CRE 2 # 63).

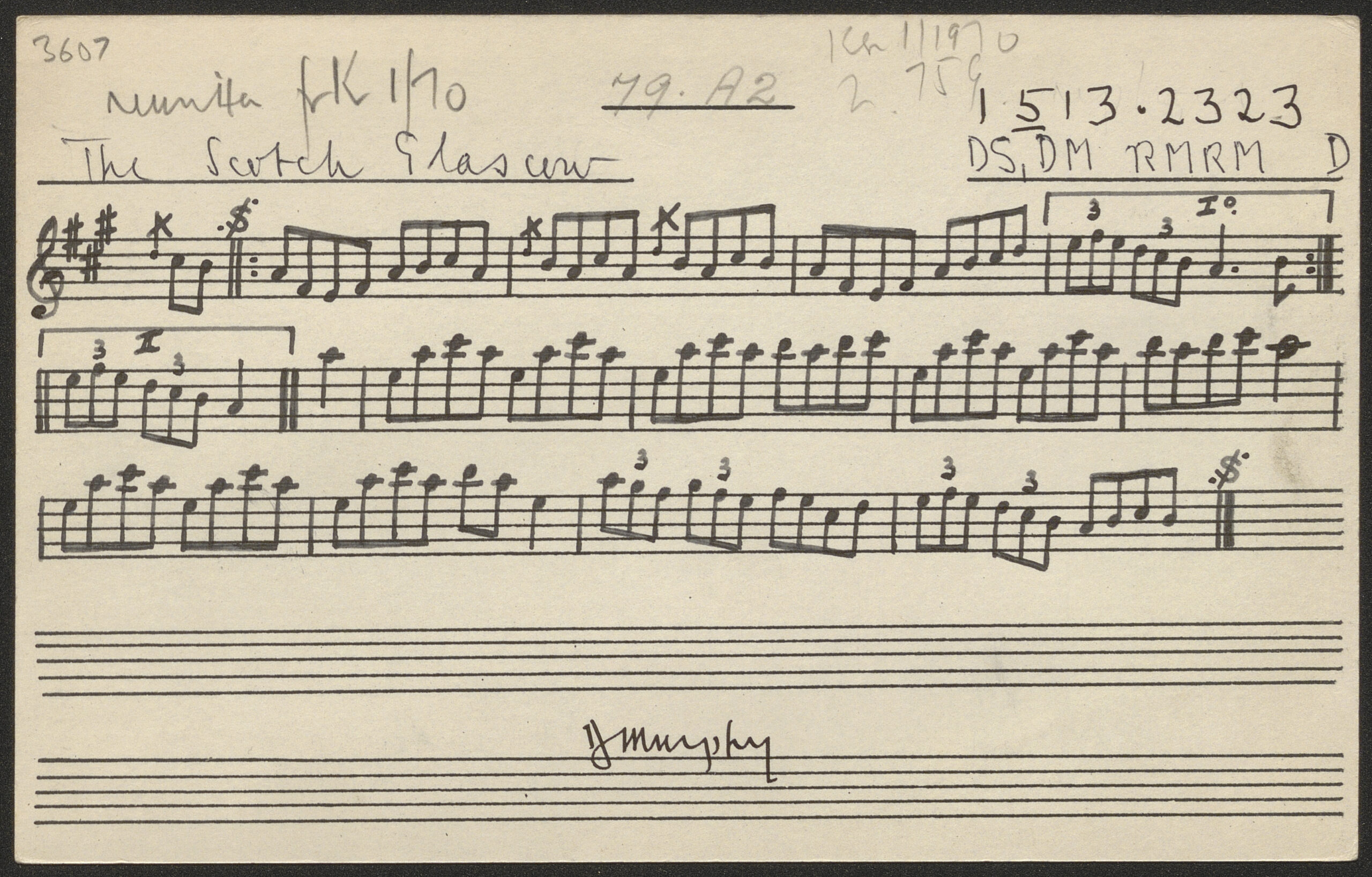

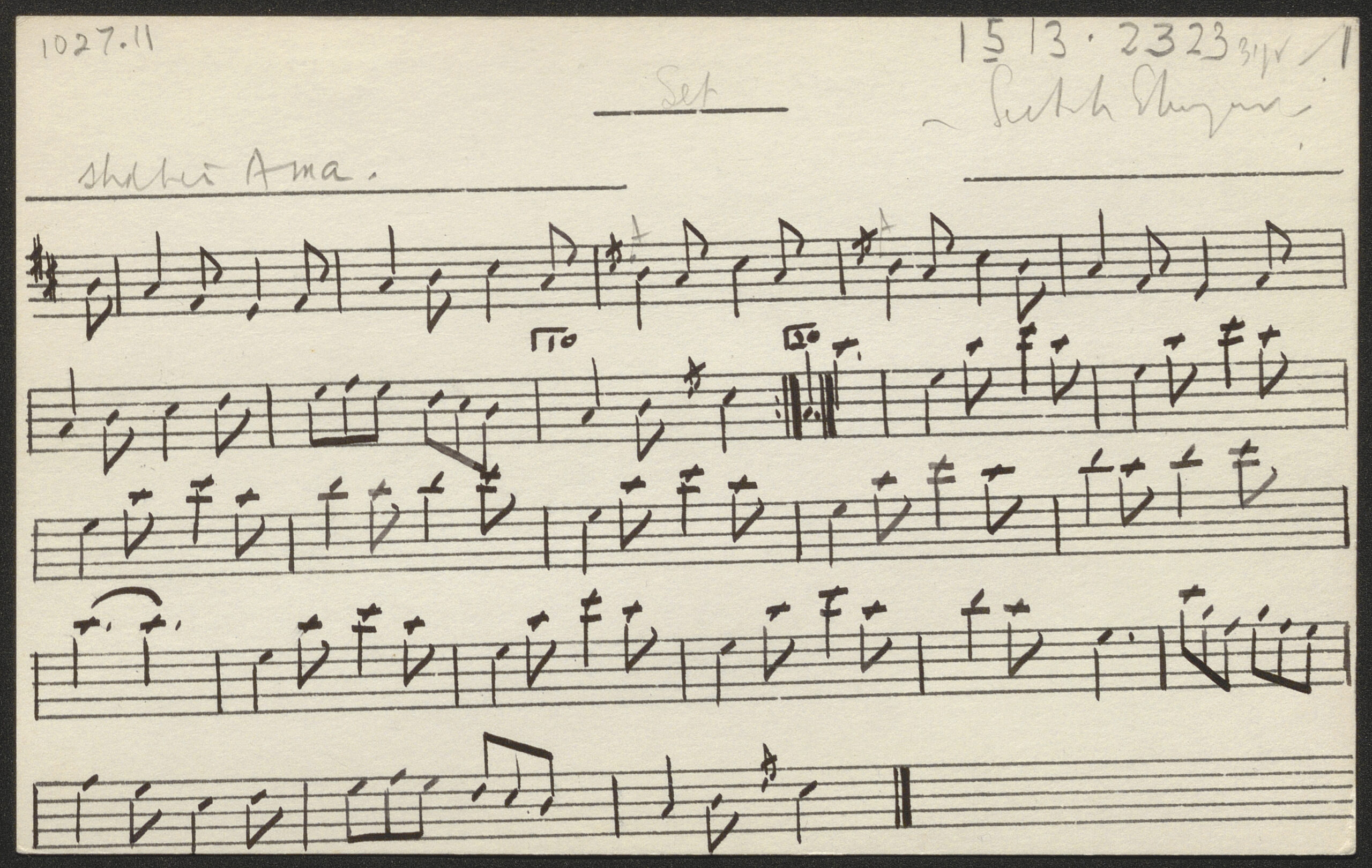

Another tune that might initially resemble Maggie Pickens but soon veers off in a very unexpected direction is the fling given the bizarre title of The Scotch Glasgow on CICD 3607. The tune, played by Denis Murphy in the key of A major, is notable for requiring the use of higher positions on the fiddle. It clearly proved to be a head-scratcher for Breathnach as he attempted to transcribe the tune three times using two source recordings of Murphy made in October 1966 and November 1970.

Breathnach interpreted the Scotch Glasgow as a single jig on CICD 1027.11 and then as an undefined 4/4 tune on CICD 3607 and CICD 6116. It appears in Ceol Rince na hÉireann 5 (no. 218) as a hornpipe and without any name attached. Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh would go on to record this tune as Denis Murphy’s quirky fling (Deadly Buzz, self-published, 2011) while Billy Clifford and Gerry Harrington recorded it without a specific name (Donal O’Pumpa Set, no. 3 – Now She’s Purring, self-published, 2018). It remains a mystery where Murphy himself learned this tune and what dance, if any, he would play it for.

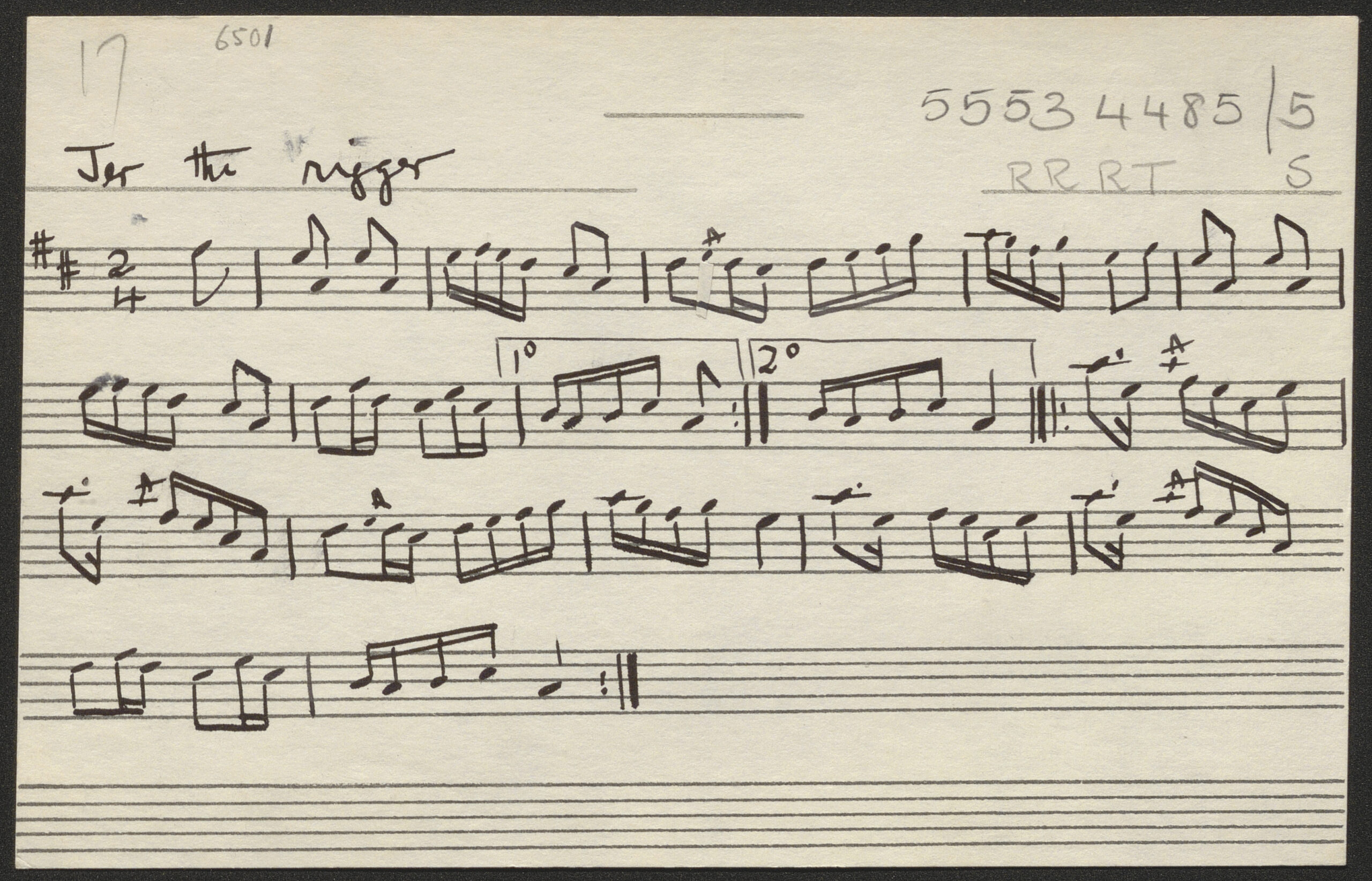

A tune does not have to be obscure to keep defying tune type boundaries for years, as is the case with the widespread 2/4 piece Jer the rigger (Ger the rigger). It was included in Johnny O’Leary of Sliabh Luachra (no. 113) as a hornpipe and was indeed played by Denis Murphy and Johnny O’Leary as a sort of a hornpipe / barndance tune, often at lively tempos. Alternatively, the tune has been identified as a single reel by Alan Ng of the Irish Traditional Music Tune Index. In many Irish music sessions around the world, though, it is regarded as a polka.

Breathnach published Jer the rigger in Ceol Rince na hÉireann 2 (no. 128). While there are no notes specifying how Murphy himself identified the tune, the Breathnach materials reveal the story behind the tune’s title. It notably contradicts all the explanations connecting it to the profession of rigging the ships – instead, the title was a reference to a nickname of a local character.

“He was an old travelling man [bringing dairies and] looking for potatoes,” explains Murphy in the October 1966 recording. “We’d give him the spuds, he’d be digging away. They called that tune ‘Jer the rigger’”.

An evening of music in Sliabh Luachra would not be complete without some banter, storytelling and a few songs. Denis Murphy certainly loved entertaining the public with short stories about Pádraig O’Keeffe and he would also introduce some tunes with pieces of folklore (including a fanciful story of The queen of O’Donnell told about the slow air Caoine Uí Dhomhnaill).

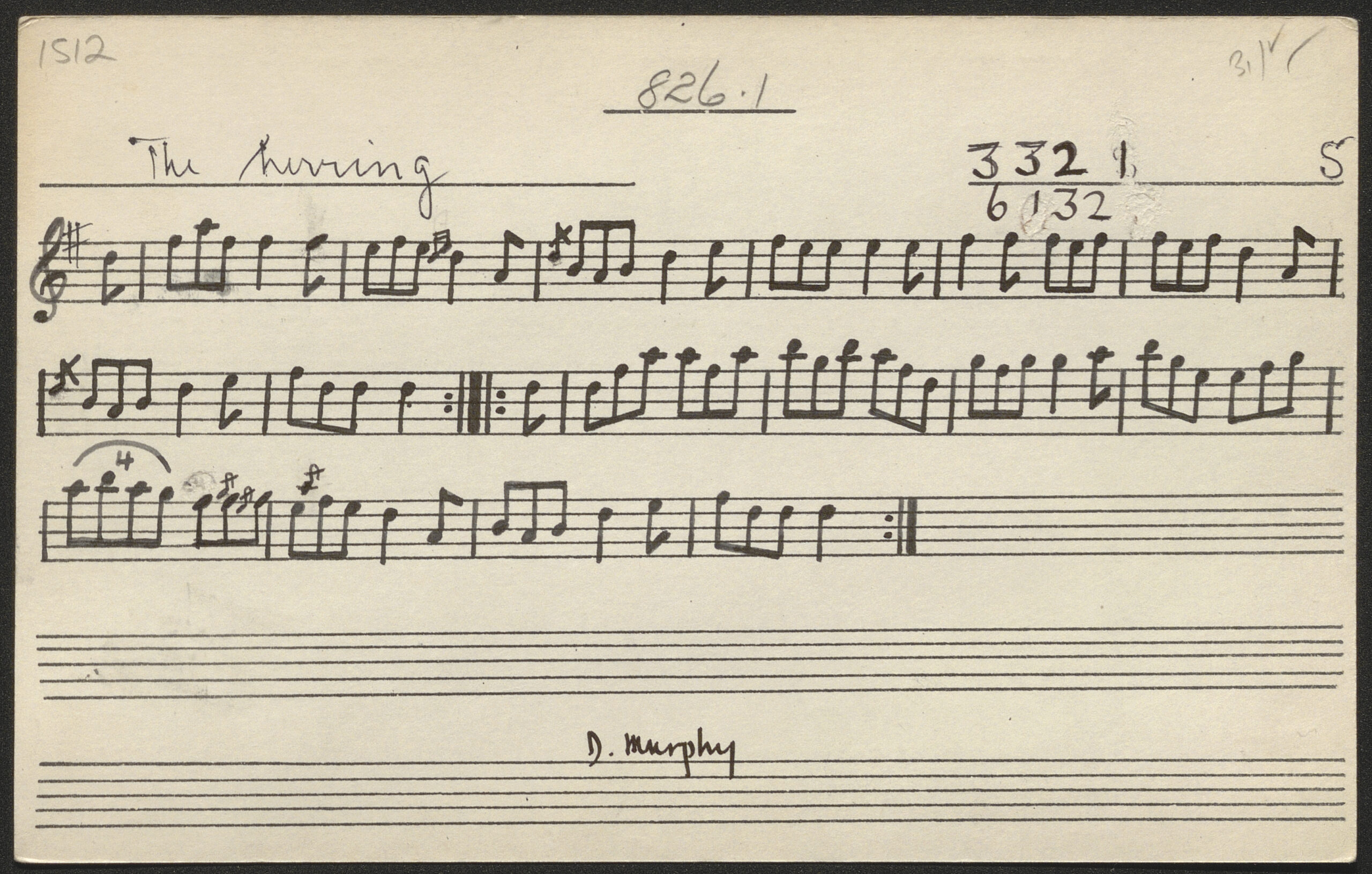

One recording made by Breandán Breathnach in October 1966 is a comic song called The herring. It is a sea shanty turned children’s song found in various versions across Britain, Ireland and North America which Murphy sang and played as a single jig or a slide. The song tells the tale of increasingly unlikely things made out of a particularly spectacular fish specimen.

Denis Murphy’s version of The herring starts the same as that of his friend Séamus Ennis’, whose shorter take on the song can be found in the Alan Lomax materials under the name The herring’s head. One notable difference is that Murphy would sometimes relocate the “old man who came from Kinsale” to Kenmare and call it a local song – a seemingly cheeky remark on a sea song for a native of a landlocked region surrounded by hills and bogs!

Yet once again, Murphy’s word on the local nature of the song seems to be perfectly validated by the recently published archival materials. Before Ennis was recorded singing it between September 1949 and February 1951, he collected this version of The herring song from the Gneeveguilla singer Sheila Cronin. According to the RTÉ Archives, Cronin’s singing was recorded on January 27, 1949.

Below are the lyrics of the song as they appear in the journal Ceol vol. 2, no. 4 with the October 1966 recording of Denis Murphy cited as the source:

I

There there was an old man who came from Kinsale;

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling,

And he had a herring, a herring for sale

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.

Sing man from Kinsale, with a herring for sale,

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.

And indeed I have more of my herring to sing,

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.

II

And what do you think they made of his head? Sing, etc.

The finest griddle that ever baked bread. Sing etc.

Sing herrine, sing head, sing griddle, sing bread, Sing etc.

And indeed I have more of my herring to sing, Sing etc.

III

And what do you think they made of his mouth?

The finest kittle that ever did spout.

IV

And what do you think they made of his back?

A nice little man, his name it was Jack.

V

And what do you think they made of his belly?

A nice little girl, her name it was Nelly.

VI

And what do you think they made of his bones?

The finest hammer that ever broke stones.

VII

And what do you think they made of his bottom?

The finest old woman that ever spun cotton.

VIII

And what do you think they made of his tail?

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.

The finest ship that ever did sail,

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.

Sing herring, sing tail, sing ship, sing sail,

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.

And I have no more of my herring to sing,

Sing aborum fane, sing aborum ling.