The Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) is committed to providing free, universal access to the rich cultural tradition of Irish music, song and dance. If you’re able, we’d love for you to consider a donation. Any level of support will help us preserve and grow this tradition for future generations.

Sliabh Luachra is a treasure trove of jigs, many of which are strongly associated with local musicians. There are numerous tunes known simply as Tom Billy’s, Pádraig O’Keeffe’s or Bill the Weaver’s that cannot be found in the early collections of Irish music and are hard to trace back any further.

Denis Murphy was a key figure in the passing down of these tunes. He would also happily share the settings of popular jigs not known outside Kerry and Cork. This is reflected in the recording sessions with Breandán Breathnach and the CICD index that contains some 40 cards with jigs collected from Murphy.

In popular mind, Sliabh Luachra jigs often get overshadowed by polkas and slides and the fact that some jigs exist in slide settings – played interchangeably depending on the context and preference – only reinforces this stereotype. In reality, jigs sometimes were the foundation of the local musicians’ repertoire. Blind fiddle master Tom Billy Murphy (1879–1944) of Glencollins Upper, Ballydesmond, Co. Cork and his famous fiddle student Molly Myers Murphy (1916–2002) were some of the most prolific jig players in the area (and, possibly, Ireland).

Jigs were also in high demand on the dance floor: popular jig sets such as The Jenny Ling (Ginnie Ling, Jenny Lind) coexisted with the Polka Set, which also included a figure suitable for jig playing (the so-called “Half Slide” – nowadays accompanied by slides by all the céilí bands).

Some of the jigs collected by Breathnach in 1966–1970 have made it to the commercial recordings of Denis Murphy, Pádraig O’Keeffe, Julia Clifford, Johnny O’Leary and others, becoming firmly embedded in the Irish traditional music repertoire. Those include two unnamed Tom Billy’s jigs (CRE 2, # 48 and CRE 2, # 31). Sliabh Luachra musicians would play those tunes for both dancing and listening, placing the emphasis on the rhythm for the former and adding intricate variations for the latter.

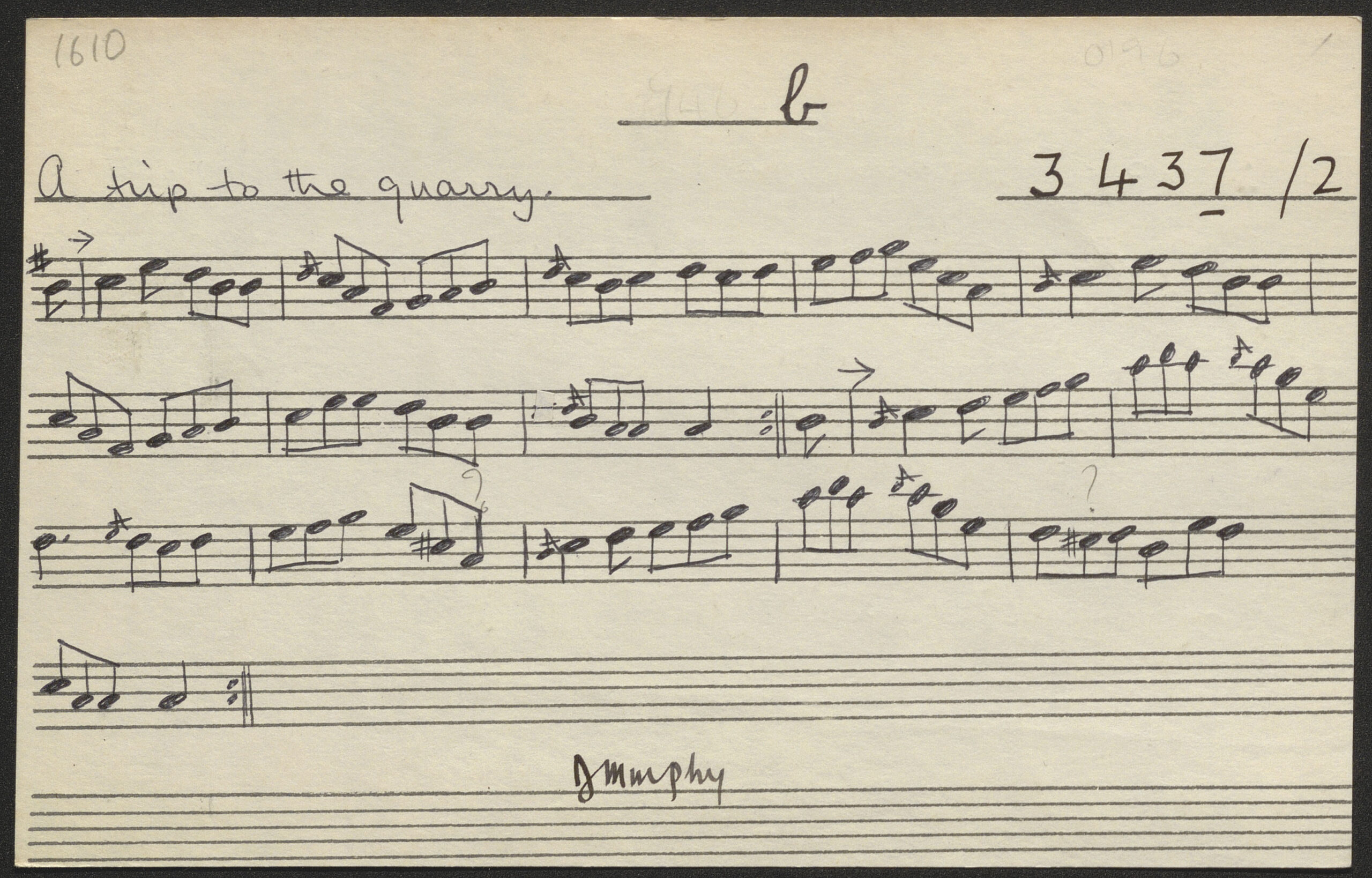

A few other jigs recorded in the area have remained in obscurity for decades before being recently rediscovered. One curious jig titled A trip to the quarry has appeared on half a dozen music albums since the start of the 21st century. The tune, which comes from Denis Murphy’s family, has most likely been saved thanks to the November 1967 recording session made by Breathnach.

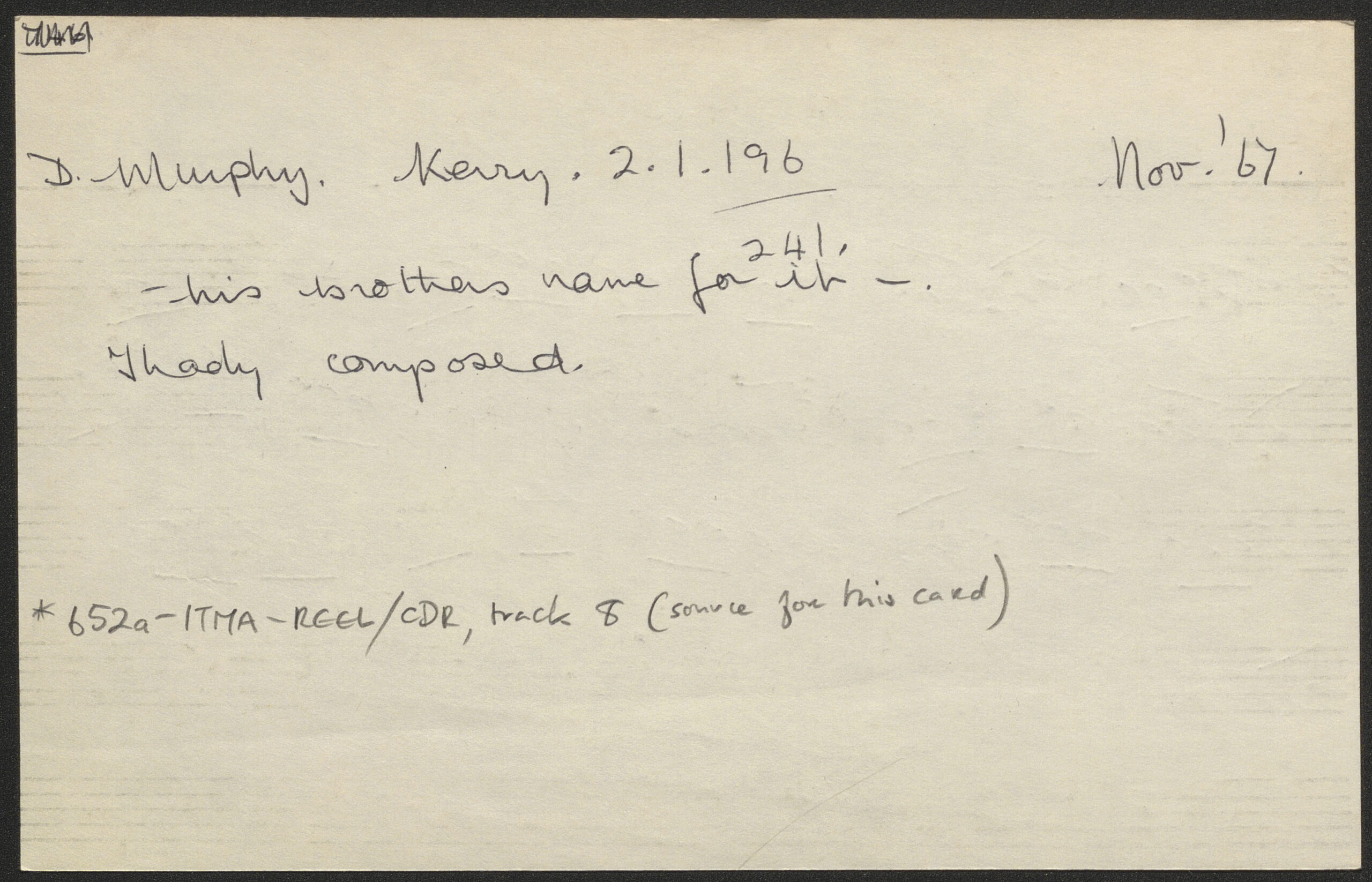

Speaking at his home in Lisheen, Gneeveguilla, Co. Kerry, Murphy says on the 1967 tape: “A trip to the quarry … my brother used to call it”. A transcription of the jig appears on CICD 1610 with a similar note made by Breathnach.

In a rare case of crediting a traditional musician in collected materials, Breathnach then adds a second note: “Thady composed”. The note is most certainly referring to Denis Murphy’s elder brother Tim “Thady” Murphy who emigrated to New York in the first quarter of the 20th century and died there in his late twenties. Coming from the musical family of “the Weavers”, Thady Murphy has been described as a skilled fiddle player, much like his younger siblings Denis and Julia. Speaking of Thady’s influence during their young years in The Journal of Sliabh Luachra (vol. 1, no. 4, 1987), Julia Clifford (1914–1997) said she learned her first tune, a jig called The ducks in the oats (CRE 5, # 58), directly from Thady.

Another jig from the repertoire of Denis Murphy and Pádraig O’Keeffe that has experienced a recent resurgence is a three-part tune called Lyons’ favourite in Johnny O’Leary of Sliabh Luachra (no. 198). The tune has been nicknamed O’Keeffe’s Morrison’s for its partial similarity to the popular two-part jig recorded by James Morrison in the 1930s. Morrison recorded the tune under the name Maurice Carmody’s favourite (CRE 1, # 50) but it was known in North Kerry as The stick across the hob. However, the Breathnach materials reveal that Murphy did not perceive it as a version of Morrison’s jig and did not call it by any of the associated titles.

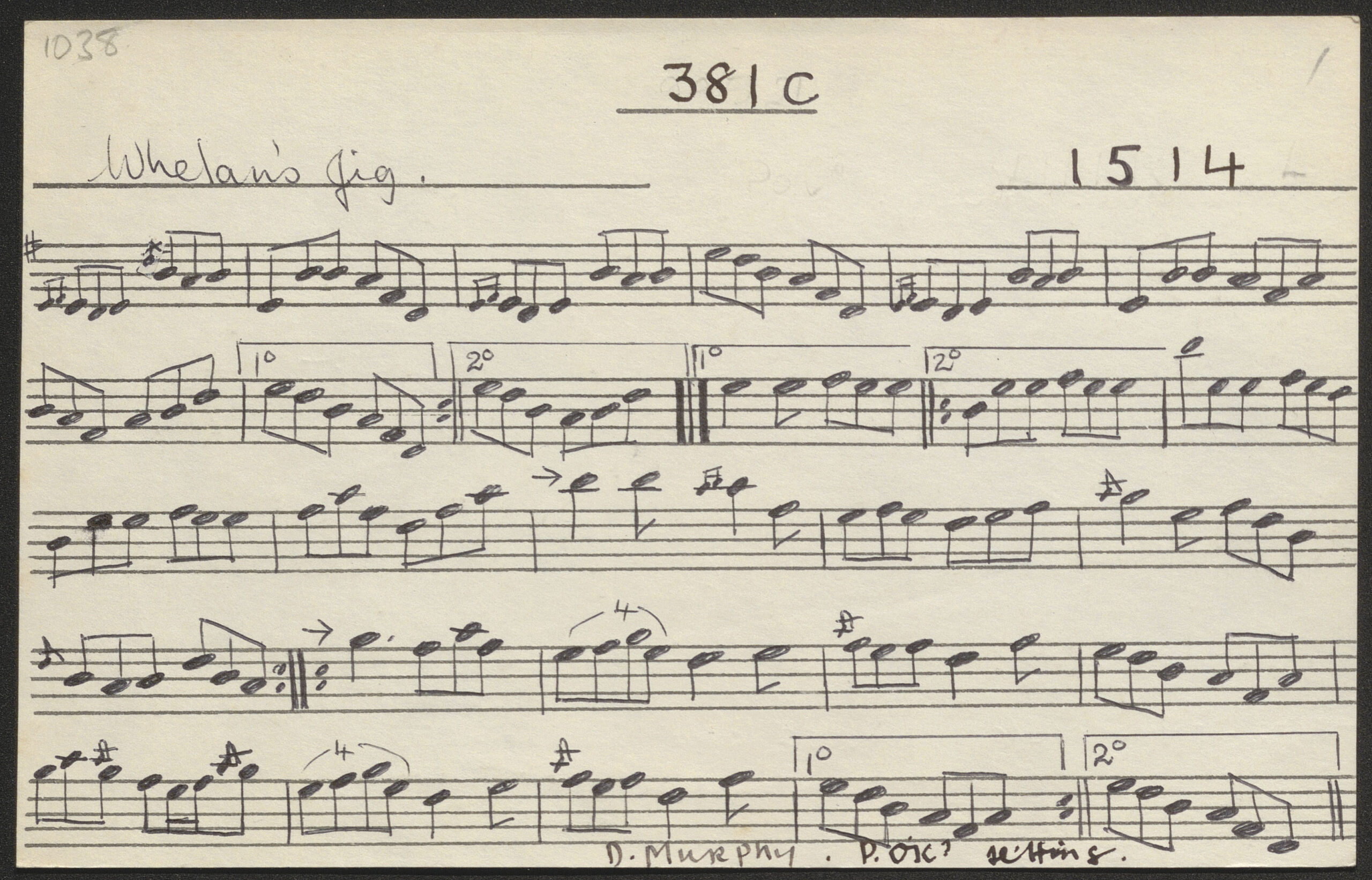

Johnny O’Leary’s title for the tune transcribed on CICD 1038 comes from the fact that he learned it from Pádraig O’Keeffe’s playing at the Lyons Bar in Scartaglin, Co. Kerry. There is a tape recording of O’Keeffe playing at Lyons’ that is well-known among the Sliabh Luachra musicians and has been partially published by the Handed Down Sliabh Luachra Audio Archive.

It includes the moment Murphy was possibly learning this jig from O’Keeffe, with the two fiddlers playing it at a slow pace after O’Keeffe’s solo. The tape is usually dated 1961 but had likely been recorded earlier in the 1950s, with multiple accounts of contemporaries suggesting that O’Keeffe’s playing ability deteriorated in the last few years of his life and he seldom played publicly.

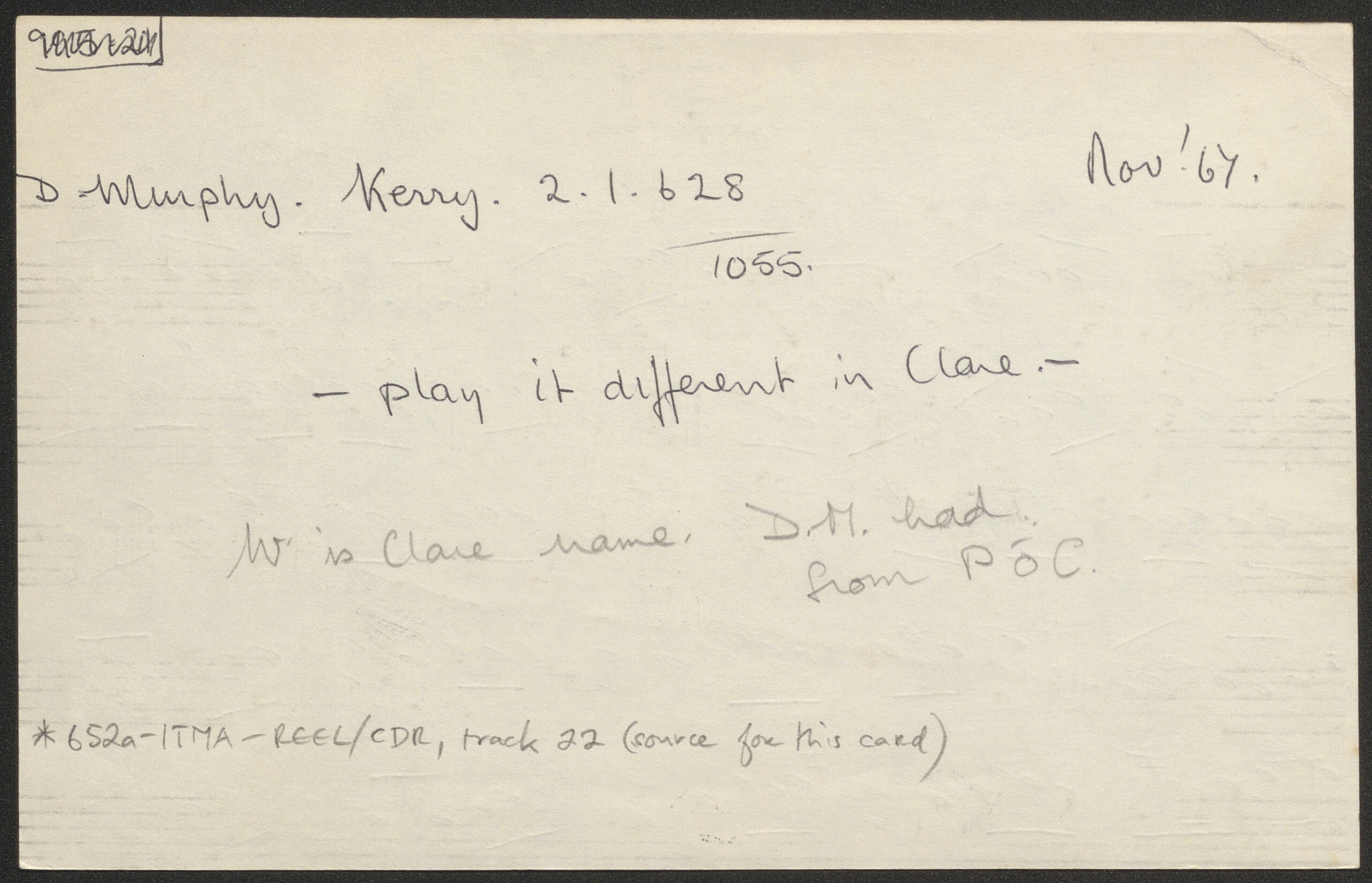

Speaking to Breathnach in November 1967, Murphy confirmed he got this jig from his old mentor, with the notes on the flip side of CICD 1038 saying “D.M. had from P. Ó C [Pádraig O’Keeffe]”. The card calls the tune Whelan’s and a note suggests it is a “Clare name” for the tune but it is played “different” in Co. Clare.

The source recording clarifies the notes given on the card: Murphy wonders aloud if the tune is a version of Whelan’s jig and then he and Breathnach discuss the difference with the Clare version. Notably, neither of the two bring up Maurice Carmody’s favourite / Morrison’s jig as a related tune. This is in contrast with the modern interpretation of the tune’s history, with Johnny O’Leary of Sliabh Luachra (1994) editor Terry Moylan and others suggesting it is “a three-part version of the tune commonly known as Morrison’s jig”.

One could argue that the first two parts of the tune are similar to both Morrison’s jig (CRE 1, # 50) and Whelan’s jig (CRE 1, # 49) and all three could have a common ancestor. It is also vital to consider the historical context, as the former jig was perhaps not as ubiquitous in the late 1960s for musicians to immediately bring it up. Regardless, not only Lyons’ favourite appears to be unique to Sliabh Luachra, Morrison’s jig also came from Co. Kerry via Morrison’s musical partner Tom Carmody. It is perhaps fitting that North Kerry-based musician and tune researcher Paul de Grae suggested using the local title of the famous two-part tune – The stick across the hob – for the three-part jig.

This is not the end of the story for CICD 1038, however, as unexpected new archival materials continue to be brought to light. In May 2024, ITMA published a never-before-heard tape of Pádraig O’Keeffe made by Paddy McElvaney in Lyons’ Bar, Scartaglin to accompany the launch of the music documentary series Taoscadh ón Tobar. Dated 1957, the tape (Tom Davis Collection – Reel-to-reel 116) offers rare examples of O’Keeffe introducing his tunes, including Lyons’ favourite / The stick across the hob. Before playing the three-part jig, untitled on tape, O’Keeffe suggests that he learned it from his “old friend” Tom Billy Murphy, placing the oldest known source related to Denis Murphy in Ballydesmond, Co. Cork.

A new interactive transcription of Denis Murphy’s 1967 recording can be found below.

[Tom Billy’s] Whelan’s, jig / Denis Murphy, fiddle ; transcribed by Anton Zille. (Breandán Breathnach Collection. Reel-to-Reel 40, November 1967)

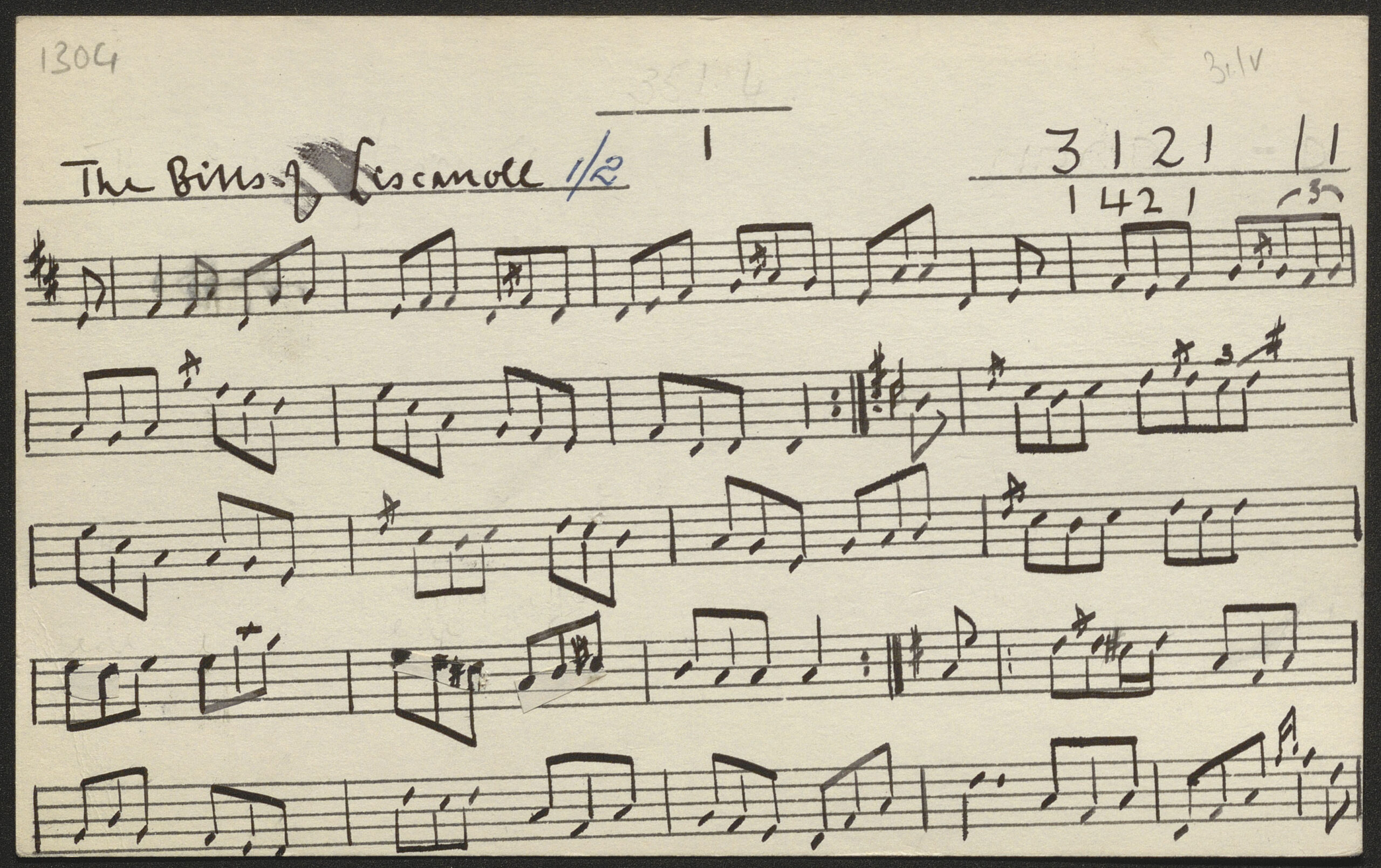

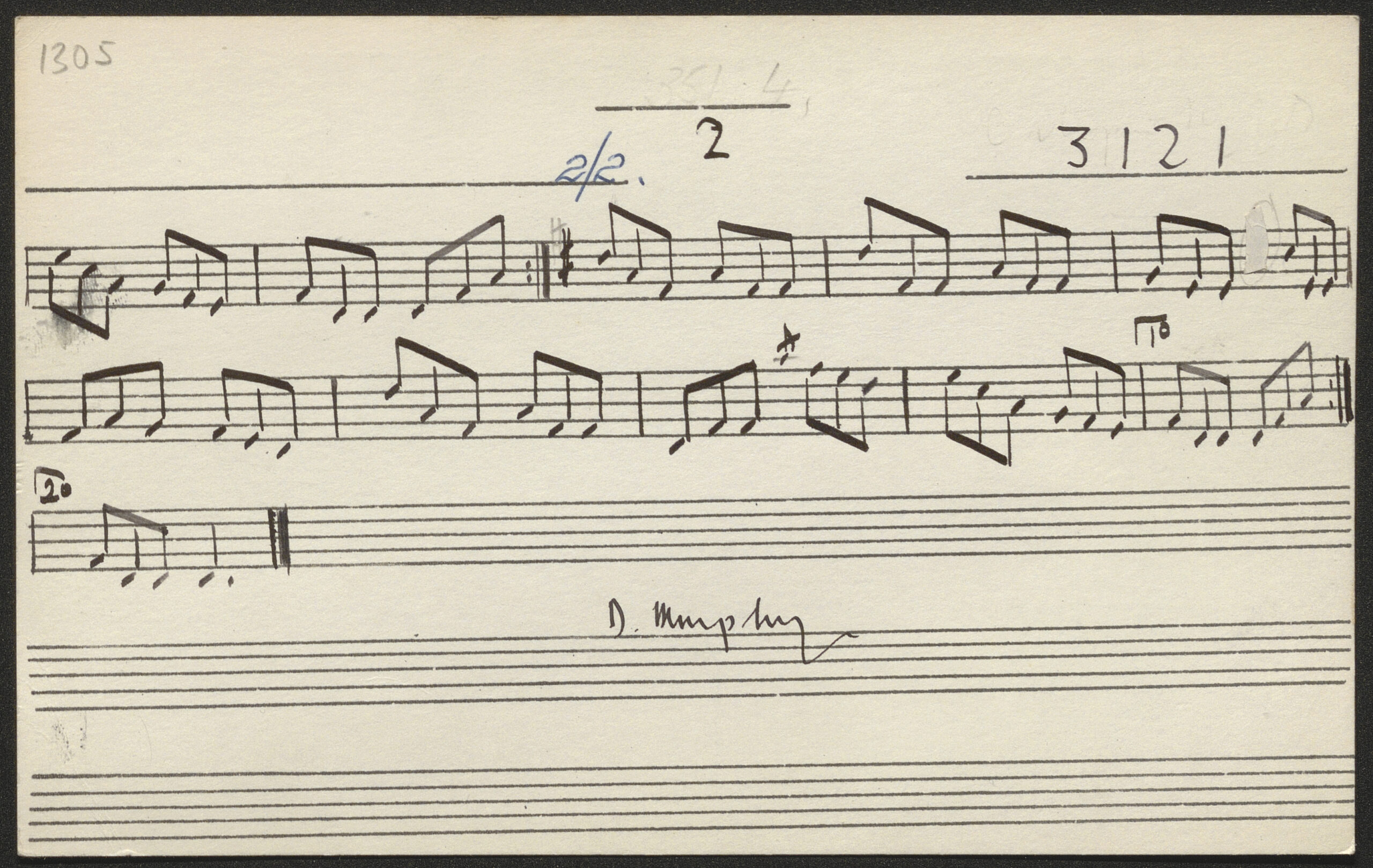

Another old jig from Denis Murphy with an interesting source is the four-part tune named The bills of Liscarroll on CICD 1304. The name on the card is likely a corruption of The belles of Liscarroll which is the title used for a related tune in Francis O’Neill’s The Dance Music of Ireland (no. 339). The latter tune is, however, a very different setting of the jig compared to the one played by Murphy in October 1966.

The setting that comes closest to Murphy’s, to the point of them being identical, is in fact in O’Neill’s Waifs and Strays of Gaelic Melody (no. 179). O’Neill took this version from the manuscripts sent to him by the London-based “Professor of dancing” P.D. Reidy. A native of Castleisland, Co. Kerry, dancing master Patrick Daniel Reidy (1844–1915?) became an influential figure in the history of the Irish step dancing through his engagement with the Gaelic League. A lesser known fact is that Reidy was an avid collector of music and sent a whole notebook of handwritten tune transcriptions, made some time in the 1890s, to O’Neill. This manuscript, which contains around 40 tunes, is now in the library of the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, United States and can be accessed online.

The jig in question is called The old walls of Liscarroll in Reidy’s MS, probably in reference to the ruins of the 13th-century Liscarroll Castle in Co. Cork. Reidy’s source for the tune was fiddle player Daniel Kelleher from Clonough, Castleisland. While there are no notes indicating where Denis Murphy learned this tune, it is tempting to speculate that it remained in the local repertoire almost unchanged. The alternative is that it may have been reintroduced to Sliabh Luachra via the transcription of the music from the area which is equally fascinating.

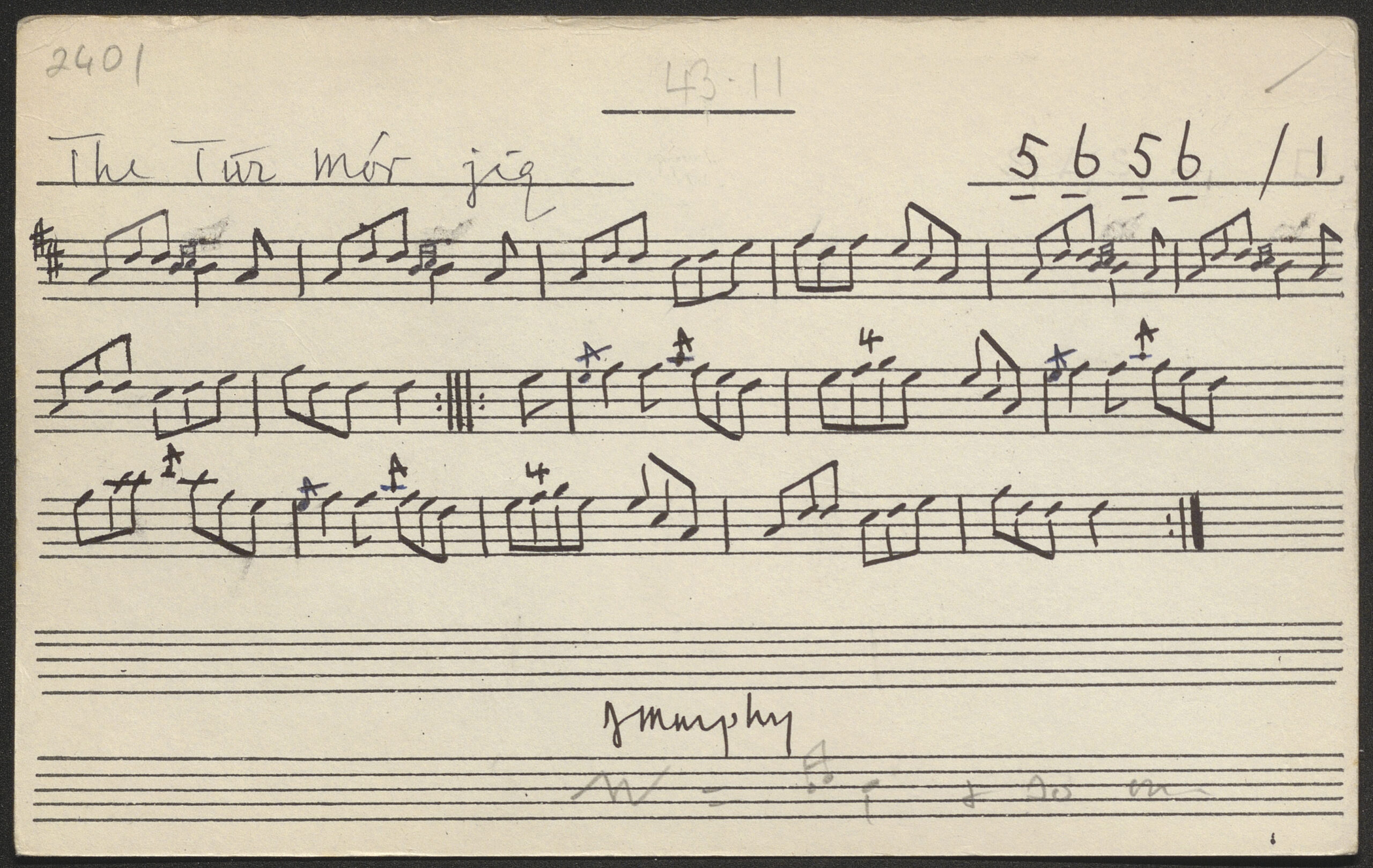

More tunes from the P.D. Reidy MS can be found among the Breathnach recordings of Denis Murphy albeit in different settings. A jig called The oak stick in the MS, which fiddler Daniel Kelleher apparently paired with The old walls of Liscarroll, is a version of a tune Murphy played in the higher key of D in November 1967. Transcribed on CICD 2401 it bears the name of Túr Mór (An Tuar Mór; Toormore), a townland near Kilcummin, Co. Kerry.

Denis Murphy’s rendition of The Toormore jig has been included in Ceol Rince na hÉireann 5 (no. 52) with editor Jackie Small pointing to several other related tunes such as the jigs called Better than worse and Foxy Mary collected by James Goodman (1828–1896) and included in the Tunes of the Munster Pipers.

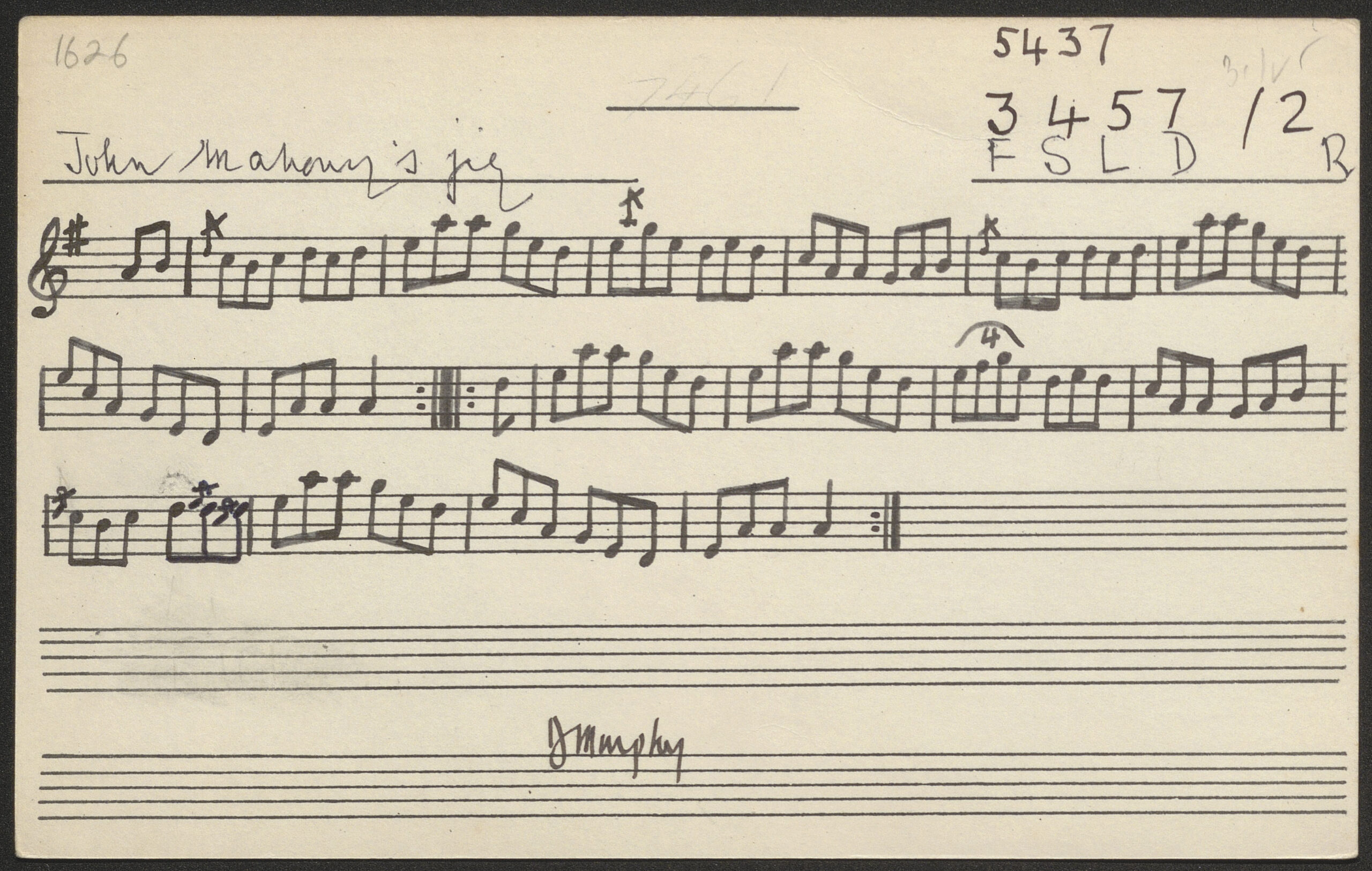

There are times when research into Denis Murphy’s tunes presents unsolved mysteries; such is the case with John Mahony’s jig played by him in October 1966 and transcribed on CICD 1626. The tune is partly similar to the jig Lucy McKenna / Luigseach Nic Cionnaith (CRE 1, # 25) but no complete matches could be found in music collections at the time of writing.

However, it could be said with some certainty that the name given by Murphy for this jig refers to the Gneeveguilla musician John Mahony (Mahinney). In a booklet accompanying Topic Records’ Music from Sliabh Luachra series of recordings, Alan Ward names John Mahinney Barnard as the source for several tunes played by Julia Clifford. Mahinney (sometimes spelled as Mahony or O’Mahony) is said to have been a friend of Bill Murphy, Denis and Julia’s father, making him a likely early influence on their repertoire and style.

The chief role in the Lisheen siblings’ musical upbringing was no doubt played by Bill ‘The Weaver’ himself, who was described as “stone mad for music” by Julia Murphy Clifford. While there are sadly no known recordings of the Murphy family patriarch’s playing, there are a few tunes referred to as Bill the Weaver’s (or Bill the Waiver’s) in the area. One of those tunes was titled Bill the Waiver’s No. 1 in Johnny O’Leary of Sliabh Luachra (no. 60).

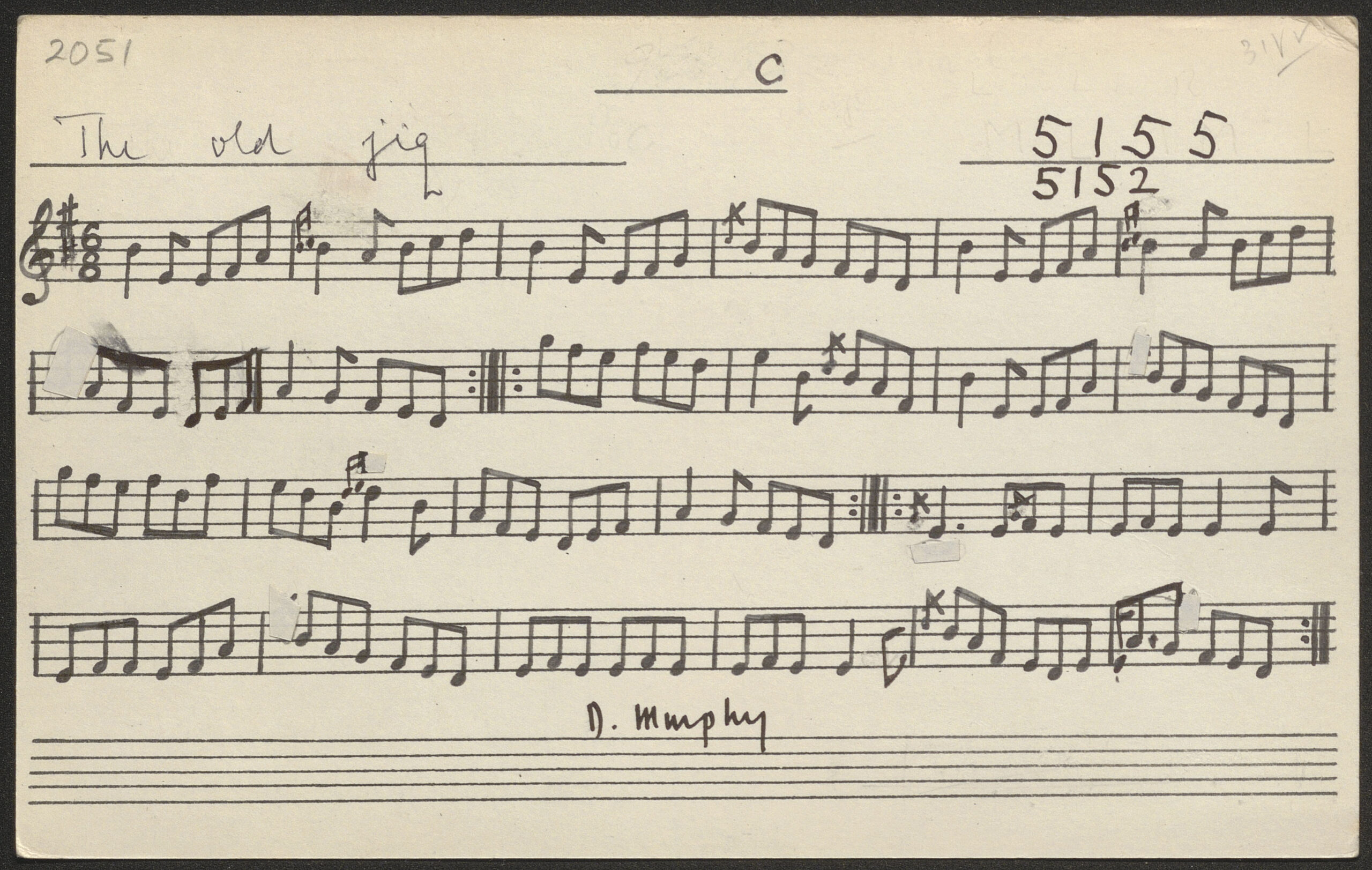

According to CICD 2051, Denis Murphy simply referred to this tune as The old jig. A version of the same jig was included in Ceol Rince na hÉireann 1 (no. 54) under the title of An seanchaí Muimhneach, or The Munster storyteller, with fiddle player Denis Cronin (Donncha Ó Croinin) serving as the source for Breathnach.

An apparent relative of this jig was published under the title of The humours of Ballinamult in the early 19th-century O’Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, making it an “old” tune indeed – but where exactly the Murphies learned it will likely remain a mystery.

It is worth noting that The old jig / An seanchaí Muimhneach is sometimes interpreted as a single jig or a slide and notated in 12/8 due to its seemingly longer phrases. This applies to a few other Sliabh Luachra tunes variously referred to as jigs or slides depending on individual preference. To an outside observer this occasional jig-slide duality might suggest that slides are only a subtype of jigs – however, local musicians clearly differentiate between the two as separate tune types and have a concept of the manner each of them should be played. These conclusions may be based on the patterns, the rhythm and the general feel of the tune but there is an additional aspect of the tune’s origin that could be considered. The Slides chapter discusses a variety of sources for these tunes – many of them apparently not based on jigs or music in 6/8 in general – which may have been transformed into dance music no sooner that the age of the Quadrille but have since become an equally vital part of the traditional repertoire.